Assessing a person’s “ripeness” for changing their behaviors is a critical first step before investing in further. As the Buddhist saying goes, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” All of us have at least one area in our lives in which we are resistant to change. Our “ripeness” varies by task, not by individual.

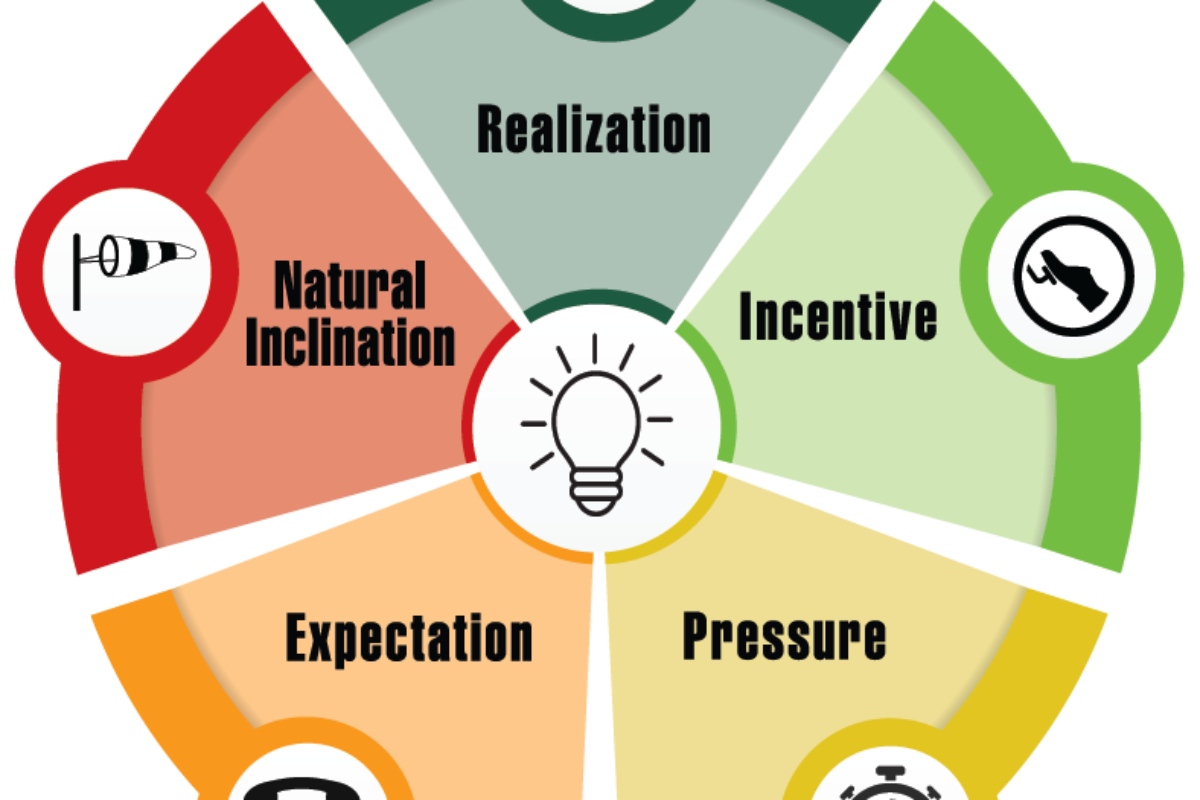

Our RIPEN model

Below are five questions to assess how “ripe” a person is for change.

R (Realization)

Does this person realize that s/he needs to change this particular behavior?

This often seems like an obvious question. Many of our clients respond, “Of course so-and-so knows they needs to change — I’ve told them that!”

But the question is not, “Have you given this person feedback?” The question is whether the person takes the feedback seriously and takes ownership over it.

If you are giving feedback and you get a response such as, “Okay, I know something needs to change, but it’s not my fault,” or, “People think that? That’s completely contrary to my motivations,” then this person hasn’t taken ownership for his or her behaviors. Remember it’s not about asking people to change themselves, but to adapt their behaviors.

There are many strategies for how to help people come to their own realization — to have a “light bulb” moment — but in general, it’s far more effective to lead them to it by asking guiding questions instead of forcing it upon them, which tends to trigger defensiveness. Get people to focus on what they can control and take ownership over instead of all the things they cannot.

I (Incentive)

Is this person motivated to change this particular behavior?

Again, this seems like a simple question. But it’s more nuanced than it seems.

There are two types of incentives. There are the incentives to change: it could be a positive incentive to gain something (e.g. a promotion) or to truly live out one’s values and beliefs, or it could be a negative incentive to avoid something (e.g. embarrassing oneself in front of a client). Either way, the person feels the motivation to change. Think of this type of incentive as the “ignition keys” that rev an individual’s engine for change.

But there are also “counter-incentives” that prevent people from changing; they are the “parking brakes” on a car. When people aren’t changing their behaviors, chances are that they are doing it for a good reason. The status quo is working for them in some way that needs to be understood and explored. Fear of failure, complacency, and fear of change are common counter-incentives.

Whatever the situation is, examine what naturally motivates a person to change (not what you think should motivate them) as well as their counter-incentives to not change. And then think about what you could do to encourage the former and address the latter.

P (Pressure)

Does this person believe s/he needs to make this behavioral change immediately?

Even if a person reaches a Realization and all the Incentives are lined up, they may not get around to changing their behavior and may instead choose to focus on other priorities. That’s because this person doesn’t feel sufficient “pressure” to make necessary changes. In other words, there is no “narrowing window of opportunity” or “pressing deadline” that is at the forefront of this person’s mind.

One under-appreciated pressure driver is a change in situations. For example, when a person is presented with a big client opportunity or is hit with a big organizational change. Reflect on what conditions would need to be in place for this person to start accelerating their journey of change.

E (Expectation)

Does this person feel confident that s/he can successfully change XYZ behaviors?

Sometimes what gets in the way of change is not a lack of motivation, but simply a lack of confidence: that is, a lack of confidence in one’s ability to achieve a certain goal. The good news is that raising a person’s expectation or confidence is fairly straightforward: It entails equipping people with the right resources (e.g. books, classes, role models, managerial support) that will help them improve their skills and/or change their behaviors.

The catch is that this element of the model tends to be overly relied upon. Many people jump to this right away by directly mapping out for someone the step-by-step plan for change and giving them a pep talk to build their confidence. That is all well and good if someone is asking for guidance and already feels an urgent need to change. Until then, your advice will likely not make a big impact. But once you feel someone has met the “R,” “I,” and “P” criteria for change and is seeking out advice, then it’s time to get to work and help them map out a plan for how to make the desired changes.

N (Natural inclination)

Does this person see her/himself as someone whose strengths and weaknesses are “fixed” or “open to change”?

If the answer is “open to change,” then this person has a “high” natural inclination for change. People with a high natural inclination see themselves as someone whose weaknesses can be improved, whose strengths are a result of a lot of hard work, and who seeks out avenues for self-improvement. Having high natural inclination acts as a “tailwind” that accelerates the pace of change—this person is likely to be curious about and open to change, and much less defensive about any feedback.

If the answer is “fixed,” then this person has a “low” natural inclination for change. People with such an predisposition may be very talented and successful, but they see their strengths as natural talents they’ve always had and accept their weaknesses as inherently part of who they are. These people tend to be resistant to constructive feedback and are reluctant to get outside their comfort zone. Their low natural inclination acts as a “headwind” that will make their journey towards change much slower and more difficult, but certainly not impossible, especially if all the other elements of the model are present.

These five elements constitute a model for understanding if someone is “ripe” for change. As you can see, a person’s “ripeness” level is not static, but rather dynamic. How “ripe” someone is for change can fluctuate depending on a number of factors, from pressure to incentive to expectation and so on. When we are “ripe and ready,” then the gears of change will finally begin to turn. As a result, “ripeness” is task specific.

The RIPEN model was first introduced in our best-selling book “How Leaders Improve” http://bit.ly/HowLeadersImproveBook and is explored in greater detail in our recently released best-seller “Ready, Set, RIPEN!” http://bit.ly/ReadySetRipenBook.

We help our clients to learn and adopt the RIPEN model in their efforts to develop others. Business leaders, what tools have you used to help an employee change their behavior? How do you think the RIPEN model can be incorporated into future coaching experiences? For more about Avion Consulting and our books, visit https://avionconsulting.com/. We also invite you to join the #AvionConsulting newsletter for further discussion at http://bit.ly/AvionNews.